Planning – Management – Construction

The Masterpiece

Heidi Weber‘s relationship with Le Corbusier developed around his art and she constantly felt that there was more to be done and that there were new areas which required her attantion. In 1960, she conceived the idea of a museum designed by Le Corbusier, which could contain the entire collection of his plastic works, his tapestries, his seated furniture and his books. An ambitious programme of exhibitions could also be hosted here. This new challenge was motivated not only by artistic reasons but by the virtuous idea of promoting Le Corbusier‘s works at their very best within a masterpiece of Le Corbusier‘s architecture. Until this point, no one had ever proposed such a challenging concept to Le Corbusier. This intention of investing in a conceptual synthesis of arts emphasised, without any euphemistic diminution, the messianic notion of the artist‘s works which Heidi Weber wished to promote. The challenge was even greater, as, at that time, there was no private museum in Switzerland which had been realised or directed by a woman. From this moment on, the idea was developed. In May 1960, Le Corbusier began to work on the new project when he was back in Paris and he informed Heidi Weber of his agreement to construct the „Maison d‘Homme“.

More determined than ever, she invested everything she had in realising this imposing and ambitious project. In order to pay for this adventure, she sold all her goods, including her property, and she rented a small (1 an a half rooms) flat for her son and herself.

The Realization

-

First there was the roof

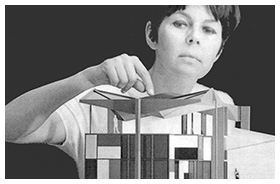

Le Corbusier usually attributed particular importance to the roof, to the point where the construction of the building actually started ‘from the roof’ down. The project was thus carried out in opposition to normal styles of construction: the roof came first and the Modulor-cubes were built or, rather, assembled, afterwards. The roof structure is independent and it is clearly separated from the corps-de-logis. It is almost like a umbrella, which protects the building from both the sun and bad weather.

Furthermore, the radical space between the pavilion itself and its roof allowed Le Corbusier to settle the divergence between two great systems which had come to be leitmotifs during the memorable time of modernism: the flat terrace roof and the inclined roof. For Le Corbusier, the terrace roof had been increasingly gaining importance, particularly as an aesthetic issue, since the old years of Maison Citrohan.

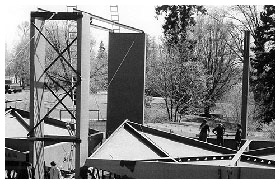

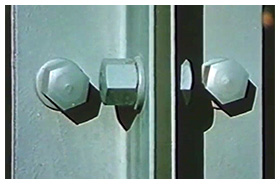

The roof of the building is the sum of all these parallel antecedents and experiments: a metallic independent roof in the form of a double umbrella. A total area of 12 x 26.3 meters, it was created using welded metal sheets that were 5 mm thick. It consists of two square parts; each part is made up of four pieces divided into two pitches. This results in a geometric figure of different slopes so that the roof assumes a greater complexity than a traditional two or four pitched roof. Given the setting - the lake and the park - the roof almost appears to be a sculpture.

As already mentioned, the interior space of the Maison d’Homme is found under this dual system of roof and terrace. It is a modular space, which has the potential to be repeated infinitely. In this sense, the roof, with its independent structure, assumes a further function: by defining the space which it covers and protects from the elements, it establishes the boundaries which regulate and limit the number of space units which can be reproduced. In this way, this method of expansion which is often presented as a versatile possibility in other projects is strictly controlled in this particular project.

The interior space is marked by a metallic structure and two cubic units. The east side of the building has two floors which are connected by a small concrete staircase and the ramp which will be explored later in more detail. The west side, on the other hand, consists of a two-storied room. On the ground floor, a large corridor connects these two areas, opening up towards the south through a large pivot door which opens onto an open space which is covered by the roof. This area contains a water basin which reflects upon the underside of the roof. This corridor can also be closed off at a certain time by means of a second interior pivot door. On the first floor, the central core comprises the concrete staircase and a small office space which is separated into an area conceived as a library. On the west side, this library area overlooks the two-storied hall. To the east, there is a single-storied exhibition hall. This division of space through the modular system is reminiscent of double space. Moreover, it is one of the key ideas in housing which Le Corbusier developed after constructing the Citrohan House and the immeuble-villa models of the 1920s and that it was captured in the Unité d’habitation in Marseille.

In this project, considerable attention is attributed to the vertical communications systems: the ramp and the stair. Le Corbusier had already combined these in other projects but he had always separated them in a radical, but simultaneously complementary, way. He captured this in his famous sentence: “Stairs separate one floor from another; a ramp joins them.” Then, after thirty years of employing the ramp at Villa La Roche-Jeanneret or of the brilliant combination of both Systems at Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier presented both devices in this project.

Furthermore, both of these systems represent the introduction of concrete into the light and basic world of metal and glass; they also suggest synthesis, a cooperation between the three greatest materials of modern construction.

The ramp is very remarkable. In contrast to the static character of the space created by the cubic units, the ramp ascends from the basement, rising up (covered) from the ground floor and then it continues upwards (uncovered and in the open air) from the first floor to the terrace. It seems reminiscent of the architectural promenade which had its highest expression in Villa Savoye. The ramp allows us to make an architectonic trip from the basement, framed by categorical concrete inside a half-lit environment (in spite of the natural light which is filtered in through various openings), to the victory of metal and glass and, finally, it reaches a communion with nature in the roof. -

August 27th, 1965 – deep mourning and standstill

Heidi Weber received the terrible news that Le Corbusier had drowned at the Cote d'Azur. Heidi Weber is deeply shocked. The structure rests ...

1964 — 1965